An Overview of Artivism

Navigating power dynamics in protest art and poetry

By Sam Downey, Arts Staff Writer

“Art should disturb the comfortable and comfort the disturbed.”

You may recognize this quote attributed to Cesar A Cruz, Harvard professor and gang violence prevention advocate. You may have even thought of it when faced by a piece of art that made you feel uncomfortable—or made you feel seen. Art has a unique cultural power to connect people of differing backgrounds, which makes it the perfect way to make political, controversial and protest-oriented statements in a language that resonates with us all.

Another reaction one might have to that quote is, it’s not that deep. And it isn’t—at least, not always. There is art that is made simply for art’s sake. But even then, there are inherent power dynamics at play: who made this, and who did they make it for? Whose voices and perspectives are elevated, and whose are not?

It used to be that only the rich and powerful could commission, collect and learn about art. While much of the “art world” remains elitist and cut off from public access, not to mention built on institutions of systemic inequality and imperialism (see our conversation with Kevin Whiteneir from last year), it has never been easier to see and learn about works of art. The internet allows you to become an expert on just about any piece, movement or artist that catches your fancy (it is important to note, however, that disparities in internet access persist, often along lines of class and race).

Even pre-internet, art made its way into the hands of everyday people through graffiti, folk art, graphic design and other undervalued art forms. These forms often inspired politically-charged pieces that commented on important social issues and pushed for change. The AIDS crisis in particular saw a rise in protest art as a means of trying to get public attention for a cause that too many people were happy to ignore (Weiner, 2018).

These days, you may have heard the word “artivism” tossed around in discussions of contemporary protest art. The term originated with the Chicano movement in Los Angeles, and has come to refer generally to the combination of activism and art across many artistic disciplines—not only visual art but also music, poetry, film and theater (Funderburk, 2021).

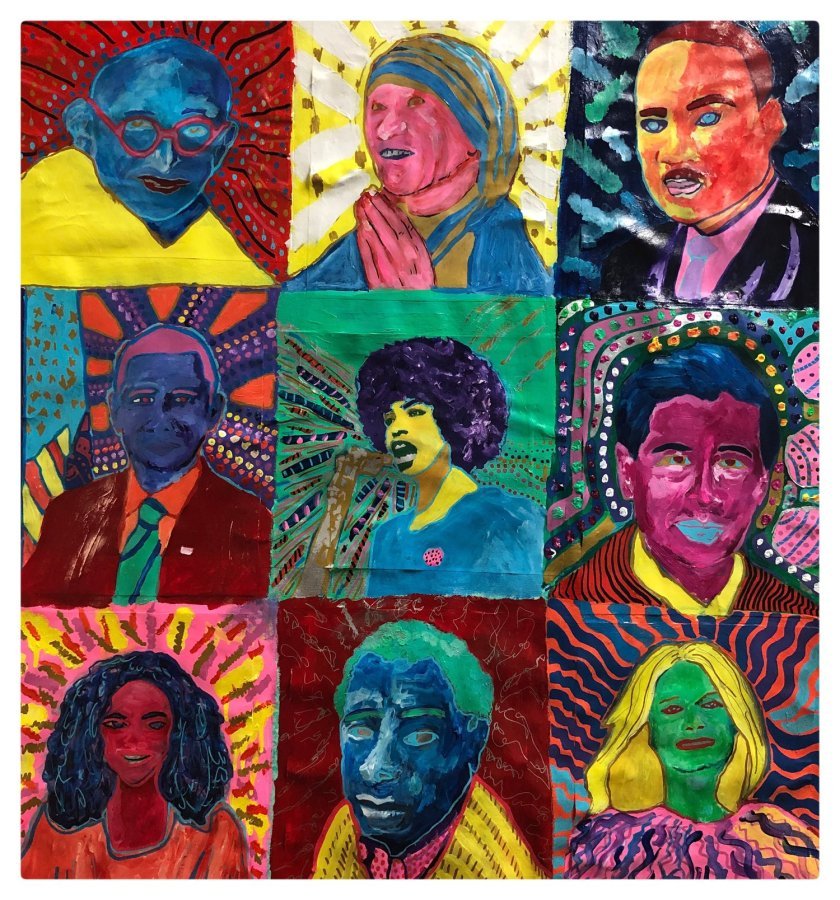

One local example is the Downtown Street Art and Mural Project, which commissioned 70 murals on and around State Street in May and June of 2020. This initiative sought to support local artists of color who lost income due to the Covid-19 pandemic, while also engaging in a dialogue with the damage suffered by several storefronts that summer. The murals are intended to call for justice and social change while sparking community conversations (PBS Wisconsin, 2020).

More broadly, artivists have stated that it is not enough to simply make art that criticizes a given institution or systemic issue: it is equally important for protest art to focus on actively getting rid of attitudes and worldviews that are rooted in those systems (Barson & Rodriguezson, 2019).

For example, central to much of artivism is the view that the personal is political. You may have seen the Audre Lorde quote: “poetry is not a luxury. It is a vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of the light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action.” That is, means of expression that draw on feelings, as poetry does, are just as important as those that draw on rational thought. Historically, oppressed groups such as women and people of color have been labelled as over-emotional in an attempt to justify their subjugation by more “rational” groups (usually white men). Lorde argues that this makes emotional expression all the more essential to envisioning new forms of activism and change (Lorde, 1977).

Though this quote can be generalized to other forms of art, poetry in particular plays an important role in artivism. The word might evoke ideas of dense sonnets by old dead guys, but contemporary poetry has been and continues to be concerned with social justice issues and the decolonization of the literary canon.

Poetry can feel inaccessible, it’s true. For that matter, it can sometimes be difficult to derive meaning from contemporary visual art. You might be driven to wonder why the poet or artist doesn’t just come right out and state their message, especially if it’s of political importance. Each artist will have their own reasons for creating work the way that they do, and the particulars of each piece are obviously going to be unique. However, the way I see it is this: art that makes the audience think for themselves will always be more powerful than art which hands the message to you on a silver platter. If you take a minute or two to puzzle over a poem or a painting and feel the pieces click into place yourself, that epiphany will be much more meaningful, and the message will likely stay with you longer.

Art, then, has the power to guide audiences into states of clarity, grief, shock or empathy, which is what makes it such a powerful method of achieving social and political change.

Not all art is artivism, it’s true. But you can always stand to gain from asking yourself, as you contemplate a poem, painting or potential purchase: Who does this empower?

For those who want to learn more:

I highly encourage you to check out the work of some contemporary poets like Natalie Diaz, Jericho Brown and Joshua Jennifer Espinoza. There are also ongoing Wisconsin Book Festival events hosted by the Madison Public Library, both in-person and virtually—I recommend checking out the “equity and social justice” category! If visual art is more your thing, there are some upcoming exhibitions at the Chazen that may strike your fancy. And finally, if you’re an aspiring artivist yourself, the UW Division of the Arts’ Artivism Student Action Program fund is a great opportunity for marginalized students!

Sources:

Barson, B. & Rodriguezon, G. (2019, September 5). Artivism and Decolonization: A Brief Theory, History and Practice of Cultural Production as Political Activism. NewMusicBox.

Cruz, C. Cesar A. Cruz Author Page. Goodreads.

Funderburk, A. (2021, May 17). Artivism: Making a Difference through Art. Art & Object.

Lorde, A. (1977). Poetry Is Not a Luxury. Chrysalis: a Magazine of Female Culture.

(2020). State Street Mural Project. PBS Wisconsin.

Weiner, J. (2018, May 4). The Art of the Aids Crisis: Cautionary Oeuvres From the 1980. CCTP 802 Art and Media Interfaced.