Behind The Cute Little Figures

Keith Haring’s legendary impact on social justice art

Written by Emma Goshin, PR and Outreach Director

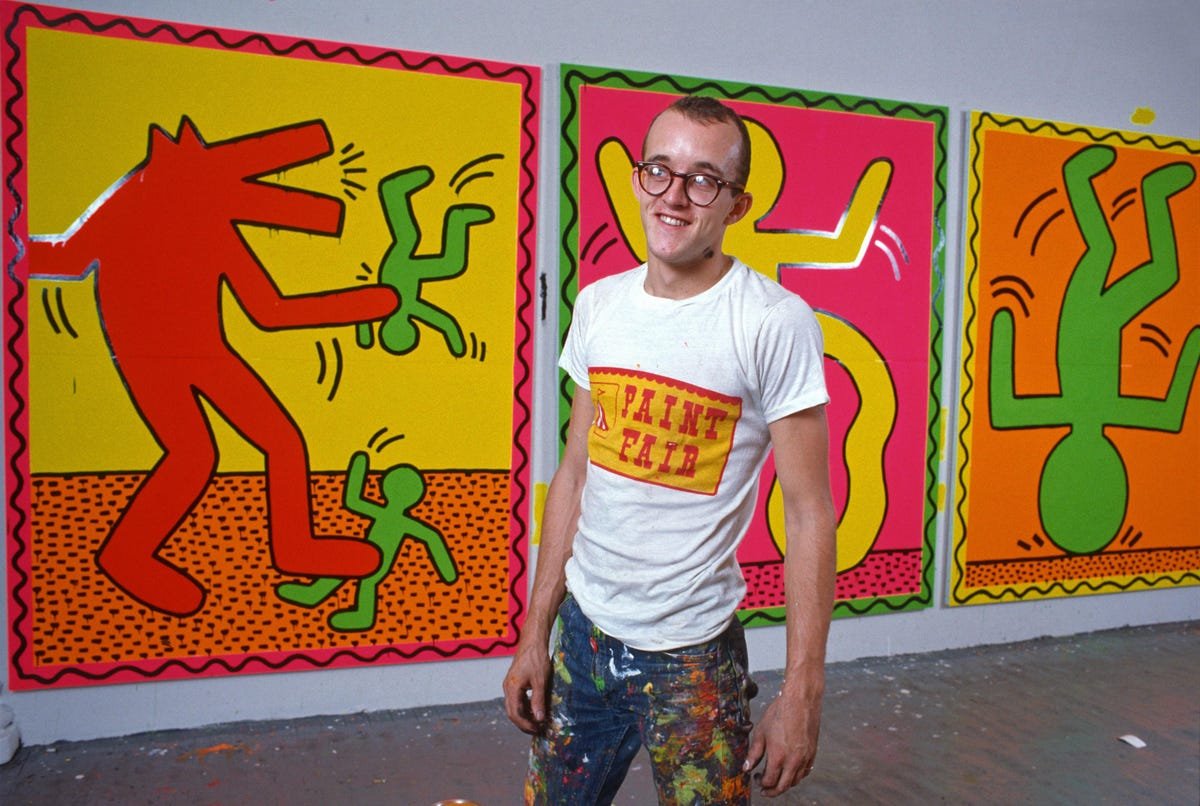

A 1980s New York City art icon, Keith Haring's unique style and artistic purpose drove him to remain a token of social justice art, even 30 years after his death. Today, you can find his art on prints and murals as well as in stores like PacSun, Urban Outfitters and Levi’s. It is vital not only to enjoy his work, but to know and recognize the background of Haring’s work, and why he created what he did.

Keith Haring used his art to speak on 1980s issues like nuclear disarmament, apartheid, environmentalism and inequality. “He was publicly minded. His art faced outwards. He wanted to inform, to start a conversation, to question authority and convention, to represent the oppressed. Those cute figures are political,” (Sawyer, 2019).

During his career, Haring’s work was featured in over 100 exhibitions. He was also the subject of 40 newspaper articles in 1986 (Keith Haring Foundation, n.d.). He collaborated with tons of artists to push his human rights messaging forward, including Madonna and Andy Warhol. Today, you can find his timeless art in Pisa, Berlin, Paris, Melbourne and of course: New York City.

Keith Haring’s work is an emblem of 1980s New York activist culture. As AIDS cases rose in the early 1980s, so did homophobia (Ruel and Richard, 2006). The media spread the notion that HIV was a “gay plague” and contributed to the popularity of the idea that gay men were disease-ridden (Howard and Yamey, 2003). Haring was a proponent of sexual freedom, and before he died of AIDS-related disease in 1990, the epidemic greatly shaped his work.

In his “Ignorance = Fear” piece, Haring presents three figures all with pink X’s on their chests to represent people affected by AIDS. They cover their ears, mouths and eyes because they are afraid to speak up out of fear of stigma (Ellis, 2017). At the bottom, Haring writes “Silence = Death” to call attention to the lack of awareness and research about the disease, which would ultimately lead to the deaths of thousands of individuals affected by it. Lastly, Haring used the pink triangle, which singled out people for queerness during the Holocaust, to flip this narrative and make it an empowering symbol (Ellis, 2017).

Today, more than 1.2 million people in the U.S. live with HIV (The HIV/AIDS Epidemic, 2021). The government was slow to fund research to treat AIDS patients, but due to the persistence of Haring and other AIDS advocates, we now have the technology to protect the health of people living with HIV and prevent disease progression and spread (U.S. Statistics, 2022).

One of Keith Haring’s most legendary pieces of work is his “Crack is Wack” mural, graffitied on a Manhattan handball court in 1986 (Cox, 2015). The crack epidemic, which had a disproportionate effect on African American communities, resulted in an increase in drug-related imprisonments as well as murder rates. Ronald Reagan’s “War on Drugs” expanded U.S. prisons and intensified policing, and the prison population doubled as a result. One in every four African Americans ages 20 to 29 was incarcerated, on probation or on parole in 1989 (Turner, 2017).

Frustrated by the slow and racially targeted governmental reaction to the epidemic, Haring painted the mural without legal permission. Though a police officer caught him, he got off with a $100 fine and no jail time (Cox, 2015). A week later, Haring’s piece was vandalized and turned into a pro-crack mural (Israel, 2014). However, the City Department of Parks commissioned him to come back and recreate the mural, which is now protected by the Department (Cox, 2015).

Before his passing, Haring created the Keith Haring Foundation to provide funding to AIDS organizations and children’s programs, as well as expand Haring’s audience (Keith Haring Foundation, n.d.). In 1989, Haring himself gifted a logo to Best Buddies, an international nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting inclusion for people with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (Best Buddies, n.d.).

The Foundation recently launched Project Street Beat, a mobile health services project to provide care for those who live with or are at risk for HIV and people who have chronic health conditions. Driving this mission further, Project Street Beat’s services are confidential and available regardless of immigration status or ability to pay (Planned Parenthood).

Keith Haring’s work is entirely dedicated to initiatives that work to help underprivileged, marginalized or underrepresented populations. We are fortunate that his legacy lives on and his art continues to break norms and push his message forth. Next time you pick up a T-shirt or hat with Keith Haring’s art on it, acknowledge what he did for so many marginalized groups and wear his art with a purpose.

Sources:

Cox, S. (2015). The Story Behind Keith Haring’s Original ‘Crack Is Wack’ Mural. All That’s Interesting.

Ellis, C. (2017). Sunny Side Up: The Positive Profundity of Keith Haring. Medium.

History of the Best Buddies Keith Haring Logo. (n.d.). Best Buddies.

Howard, K and Yamey, G. (2003). Magazine’s HIV claim rekindles “gay plague” row. National Library of Medicine.

Israel, M. (2014). Keith Haring’s ‘Crack is Wack’: NYC’s Most Famous Mural? The Huffington Post.

Bio. (n.d.). Keith Haring Foundation.

Project Street Beat. (n.d.). Planned Parenthood.

Ruel, E and Campbell, R. T. (2006). Homophobia and HIV/AIDS: Attitude Change in the Face of an Epidemic. Social Forces.

Sawyer, M. (2019). ‘The public has a right to art’: the radical joy of Keith Haring. The Guardian.

The HIV/AIDS Epidemic in the United States: The Basics. (2021). KFF.

Turner, D. S. (2017). crack epidemic. Encyclopedia Britannica.

U.S. Statistics. (2022). HIV.gov.