Damned If You Do, Damned If You Don’t

Virginity as a social construct to exploit and control women’s bodies

By Alison Stecker, Online Editorial Assistant

Having sex for the first time is a common experience, but the conditions and pressures that make up virginity are socially constructed to exploit and control women’s bodies. Before paternity tests existed, husbands needed some sort of assurance that their children were a part of their bloodline, and taking a woman’s virginity was the only way to guarantee that (Sherman, 2016). Women’s bodies were even used as a down payment for marriage, and virgin brides had higher dowries than those who weren’t (d’Avignon, 2016). Virginity stemmed from religious beliefs that commodified women, but as pop culture progressed, virginity and sex have transformed into a double standard.

The obsession with virginity originates from Mariology, the Roman Catholic worship of the Virgin Mary. Mariology began to flourish when the Byzantines spread the idea that Mary and baby Jesus were at the center of the cosmos (d’Avignon, 2016). This belief took full force during the Middle Ages, bolstering the importance of purity and establishment of chastity, or abstinence from sex. Since Mary was supposedly at the center of the universe, she adjusted the way society understood women and their bodies—women were deemed evil if they violated their purity (d’Avignon, 2016).

Queen Elizabeth I of England serves as a great example of how the purity myth is nothing new. The technicality of her virginity came into question when rumors spread about her involvement in various relationships (d’Avignon, 2016). Queen Elizabeth’s love life became the center of the kingdom not because she had multiple relationships, but because she was childless. Sex without offspring was unacceptable, so she was deemed a slut for not maintaining the patriarchy and her role as Queen.

Society’s obsession with the patriarchy evolved into the worship of virginity itself. Some women promise to stay a virgin until marriage to honor their relationship with God, while others participate in practices like Purity Balls (d’Avignon, 2016). Purity Balls are father-daughter dances where the father vows to protect their daughter’s virginity until marriage (d’Avignon, 2016). These promises reveal how paternal ownership and control of women’s bodies remain prevalent in the maintaining of virginity. However, these Purity Balls don’t always conflate virginity with innocence and don’t prevent many teenage pregnancies.

Anthony Paik, a sociologist at the University of Massachusetts–Amherst, conducted a study that analyzed how “pledge takers” become “pledge breakers.” He found that 30% of girls who made a pledge to stay celibate broke it and became pregnant while unmarried, while 18% of girls who did not promise to wait until marriage became pregnant six years after they started having sex (Khazan, 2016).

“Abstinence pledgers are more likely to receive cultural messages downplaying the effectiveness of condoms and contraceptives as well as to be exposed to the framing of premarital sexual activity as a form of failure,” Paik said. Abstinence pledges like Purity Balls perpetuate the idea that young women who engage in premarital sex are societal failures and are only valuable for their role as wives and mothers.

Purity culture can even be ingrained as life or death situations in other parts of the world. In Islamic nations, women can be a victim of honor killings if they have sex or get pregnant before marriage, not preserving family honor (Sherman, 2016).

American culture further blurs the line between sexuality and morality. The expectation that prom night is “the night” for young girls to lose their virginity puts pressure on them to have sex before they are ready. When men lose their virginity, they are viewed as “the icon” and praised by their peers. When girls lose their virginity, they are slut-shamed and frowned upon (Stier, 2016). On the other hand, if they save themselves for marriage or the right person, they are prudish or too innocent. When it comes to sex, women cannot win because they are either called easy and dirty, or uptight and pure.

The negative stigmas around virginity can follow young women into college, which may result in isolation or embarrassment by peers. With the development of the Rice Purity Test, young women compare their scores to see who is the most sexually advanced. These types of tests condemn sexuality and contribute to the guilt and shame society puts on women for having sex (Team Scary Mommy, 2021).

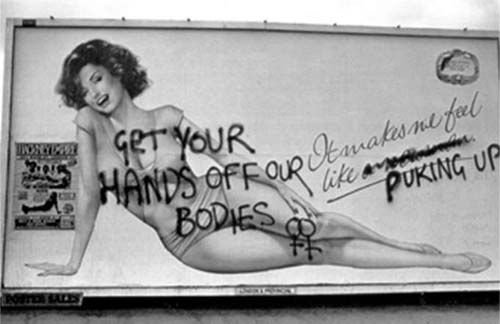

Women deserve the right to embrace sexual freedom without fear of any emotional or physical penalty. It is important to knock down these outdated stereotypes associated with “losing one’s virginity” and remind ourselves that women’s bodies are not objects for male and patriarchal ownership. Transnational movements like SlutWalks celebrate sex-positivity and call to end slut-shaming (Sherman, 2016). They believe that chaste women are not necessarily better than those who choose to have premarital sex, and they hope to end the notion that modesty, purity and abstinence make women more valuable to society.

Sources:

d’Avignon, A. (2016, May 11). Why Have We Always Been So Obsessed With Virginity? Medium.

Khazan, O. (2016, May 4). The Unintended Consequences of Purity Pledges. The Atlantic.

Sherman, E. (2016, July 21). The Untold Story Behind Humanity’s Obsession With Virginity. all that’s interesting.

Team Scary Mommy. (2021, April 21). The Rice Purity Test: Shaming Women For Nearly A Century. Scary Mommy.